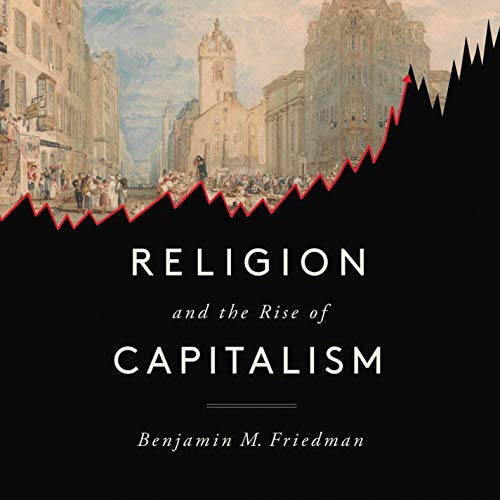

Religion and the Rise of Capitalism audiobook

Hi, are you looking for Religion and the Rise of Capitalism audiobook? If yes, you are in the right place! ✅ scroll down to Audio player section bellow, you will find the audio of this book. Right below are top 5 reviews and comments from audiences for this book. Hope you love it!!!.

Review #1

Religion and the Rise of Capitalism audiobook free

Religion has always had an uneasy relationship with money-making. A lot of religions, at least in principle, are about charity and self-improvement. Money does not directly figure in seeking either of these goals. Yet one has to contend with the stark fact that over the last 500 years or so, Europe and the United States in particular acquired wealth and enabled a rise in peoples standard of living to an extent that was unprecedented in human history. And during the same period, while religiosity in these countries varied there is no doubt, especially in Europe, that religion played a role in peoples everyday lives whose centrality would be hard to imagine today. Could the rise of religion in first Europe and then the United States somehow be connected with the rise of money and especially the free-market system that has brought not just prosperity but freedom to so many of these nations citizens? Benjamin Friedman who is a professor of political economy at Harvard explores this fascinating connection in his book Religion and the Rise of Capitalism. The book is a masterclass on understanding the improbable links between the most secular country in the world and the most economically developed one.

Friedmans account starts with Adam Smith, the father of capitalism, whose The Wealth of Nations is one of the most important books in history. But the theme of the book really starts, as many such themes must, with The Fall. When Adam and Eve sinned, they were cast out from the Garden of Eden and they and their offspring were consigned to a life of hardship. As punishment for their deeds, all women were to deal with the pain of childbearing while all men were to deal with the pain of backbreaking manual labor In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground, God told Adam. Ever since Christianity took root in the Roman Empire and then in the rest of Europe, the Fall has been a defining lens through which Christians thought about their purpose in life and their fate in death.

For the longest time after the Roman Empire collapsed, human beings engaged in toil on their farms and feudal estates without an appreciation of anything resembling what we today call the national or global economy. There was also a great deal of inequality built into this system, with landlords squeezing their serfs for all they were worth and the serfs having very little bargaining power. It was not just an unfair system but also an inefficient one, certainly for the serfs but also ironically for the landlords who were not always getting access to the best labor. Its also very hard for us today to appreciate how much of a role religion played in peoples lives then. Essentially every aspect of their existence, every transaction they made, every small task they did, was somehow justified or frowned upon by something said in the Bible. If you wanted guidance on how to do an economic transaction, you would just as easily go to your priest as to anyone else. The basic understanding that people had of their lot in life was that if it was wretched or blessed, it must be because God had foreordained it.

The Protestant Reformation started by Martin Luther in 1517 changed everything profoundly. There were two important developments that Luther ignited. One was a movement against the Church. The other was his translation of the Bible into German and insistence that ordinary people read it so that they can have a personal relationship with God that is unconstrained by the whims of priests in Rome. The Reformation made literacy rates in Europe spike; there is plausible evidence that as you moved away from Wittenberg where Luther lived and preached, literacy rates correlated with whether a region was Protestant or Catholic. This religious rift between Protestants and Catholics led to centuries of religious wars in Europe in which millions of lives were lost and the countryside decimated. It also led to economic depressions from loss of material goods and the labor force.

Luthers revolution led to an unexpected meld between religion and economics via two significant avenues. One was the second Protestant revolution started by John Calvin in Geneva. Calvinism spread like wildfire throughout Europe and particularly in England, where it fell on fertile soil just as Henry VIII was engineering a momentous break with the Catholic Church. The next few decades saw the English monarchy playing ping pong with Catholics and Protestants; starting with Mary Stuart and ending with James II and the Glorious Revolution, the Anglican Church finally became established as the mainstream church in England. A momentous impact of these developments was the migration of Puritans who were persecuted under James I and Charles I to New England. But an even more significant development, and one that was to have an unexpected impact on economics and religion, was brewing under the surface.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, a group of thinkers including Francis Bacon, Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton, Robert Boyle, Robert Hooke, Christiaan Huygens, Gottfried Leibniz and others started what was the single most important transformation in the history of human thought the scientific revolution. They showed us that the world around us can be understood and improved by doing experiments and calculations. Mathematics was found to be the language in which nature speaks. But the philosophical impact of the scientific revolution was even bigger than its specific elements. The revolution brought a mechanistic way of thinking to the forefront. Human beings were now thought to be marvelous levers in a great clockwork universe engineered by God. Its worth noting that almost all of these early scientists or natural philosophers as they were called back then were devout men of religion. Some were deists who believed that God has set the machine into motion and then stepped away from its actual workings; others believed that God continues to actively intervene. But all of them saw no conflict between their worldview of science and religion.

This mechanistic worldview was very much in the air as the scientific revolution spread to Scotland. Its beneficiary was a Scotsman who probably deserves credit for lifting more people out of poverty than anyone in human history, all through a single work of genius. Adam Smith grew up steeped in an education that included both a history of Europes religious wars and the mechanistic, Newtonian worldview. With his friend David Hume who was much more skeptical of religion than him, he wanted to see how Newtons universe could be applied to human transactions. The result was his seminal book, The Wealth of Nations, in which he carefully laid out how society could benefit entirely and unexpectedly from human beings acting in their self-interest. Most importantly, while French thinkers before Smith like Nicole and Mandeville had also explored this relationship (Mandeville citing a very charming example of a beehive), Smith actually provided a mechanism, that of the market, competition and specialization. But The Wealth of Nations along with Smiths earlier The Theory of Moral Sentiments also hinted at how competition, self-interest and the resulting societal benefits made economic transactions not just practical but also moral. Smiths opinion was that God has given each person a desire to improve not just their own lot but that of others (in his book Smith called this desire sympathies). Smiths thinking galvanized economics in Europe and spread across the Atlantic. Prophetically, his book came out four months before the Declaration of Independence was written and the American Revolution began.

But Smiths contributions still had to overcome the harsh constraints of Calvinist thinking. When the Puritans migrated to New England in 1630 to escape religious persecution, they brought with them a brand of religion that was almost as restrictive as what they were trying to escape. The essence of Calvinism that dictated both theory and practice in the New England settlements was predestination. Predestination refers to the belief that God has already decided who will go to heaven and who to hell. It also tells us that because of Adams original fall, all have sinned. The predestinarian doctrines were preached with great force by preachers like George Whitefield and Jonathan Edwards in the religious revivals of the mid 18th century. Predestination was a depressing and fatalistic idea if God has already decided where you will be in the afterlife, what could you do to change this? But, goaded by the Enlightenment, predestinarian Calvinist thinking ran up against the idea of human agency. John Locke who along with Voltaire and Newton, was one of Thomas Jeffersons heroes rejected the notion of sin dictated by Adams fall. Locke said that all men could not have been born in sin just because Adam sinned, simply because Adam never gave them his consent. Every human being thus starts their existence anew in Lockes famous phrase, as a tabula rasa or blank slate which means that everyone has the moral and practical agency to dictate their own destiny. Along with Locke, the 16th century Dutch theologian Jacobus Arminius had also rejected Calvinist predestination in tolerant Holland and his ideas were highly influential. Arminianism was the basis of Methodism which was to spread significantly in the United States two centuries later. Premillennialism thinking also played a role in seeking to improve mans condition before the great reckoning.

With the challenge to traditional Calvinism came the notion that self-love or self-interest were not antithetical to religion. This thinking was spread from the mid 18th century onwards in the United States by a number of theologians and political thinkers, including the founding fathers themselves who saw trade and economic transactions as key to growing a new nation. Calvinism was also diluted by the many other denominations including Baptist and Methodist that sprung up over the new few decades. Goaded by freedom of religion, just like the economic marketplace the United States developed a religious marketplace in which anyone was free to leave their church and join another should they find the tenets of their present church unpleasant. Not surprisingly, depressing Calvinist predestinarian doctrines of eternal damnation and hellfire started becoming unpopular. The new religious sects saw no conflict between religion and money-making. Echoing Adam Smith for instance, Francis Wayland, a Baptist who was president of Brown University said that the laws of demand and supply were an expression of Gods unity and protection. Theologians like him were going even beyond Smith who didnt try to form explicit connections between religion and capitalism.

It was also fortuitous that this questioning of Calvinism and reaffirming of a harmonious relationship between Christianity and religion came just as the United States was explosively expanding to the West and the industrial revolution was moving capital and human labor away from rural to urban centers. Opportunities for self-love were becoming limitless, and for a young country which wanted to expand its frontiers while also expanding its religious diversity, disavowing self-interest for the sake of religious objections would have been, well, a sin. But as far as sins went, there was one original sin that the growing nation was steeped in, and that was slavery. The relationship between slavery and religion is at least as complex as that between capitalism and religion; slavery was both justified and opposed on Christian grounds. But a movement that saw self-interest and demand and supply as compatible with Christianity also could not escape the inconvenient fact that slavery, while multiplying labor, also kept true demand and supply and wages muted. It might be benefiting slave owners but it wasnt benefiting society as a whole, a goal that theologians of the day were realizing more and more should be the proper goal of a Christian ethic. Not surprisingly, abolition and temperance movements soon started arguing against slavery both on religious as well as economic grounds.

By the end of the Civil War, the relationship between capitalism and religion was apparent. Henry Ward Beecher, perhaps the most famous (and soon to be infamous because of an affair) minister of his day, preached at Brooklyns Plymouth Church that was attended by New York Citys rich and famous. Beecher not only saw no conflict between making money and worshipping God, but he also had a view of income inequality that would be unpopular today. Beecher did not think inequality was a problem because in his mind, those who were poor or unsuccessful largely deserved their fate because of a lack of personal responsibility echoing a curious throwback to Calvinist predestinarian thinking, it was what God had intended for them. But views such as Beechers changed as a series of economic depressions and labor strikes, along with photographs of the plight of the poor in city tenements, made clear how wretched a system of winner-take-all could be. This was the era of the robber barons, after all. Soon both ministers and educators like Washington Gladden and Walter Rauschenbusch started to preach what they called the Social Gospel, a gospel that taught Jesuss original message of trying to love thy neighbor even when you are trying to love yourself. Many of these reformers taught at leading universities like Columbia and Dartmouth, facilitating the spread of their thinking in the new generation. Businessmen like Andrew Carnegie who also became great philanthropists further drove home how important it was for the rich to give back to society. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 and Teddy Roosevelts crusade against big business turned into law what was previously the province of writers and preachers.

In the 20th century the American Century the United States emerged as the worlds foremost economic and technological power. American self-love reached its pinnacle under Calvin Coolidge who acknowledged a truth that had been evident for a long time the business of America was business. The Depression put a dent in how well this business worked, even as World War 2 rescued it and put American economic growth on steroids. For most of this time the relationship between personal, religious and economic freedom had been taken for granted, but it suddenly became conspicuous as American faced a new foe which didnt just stifle personal freedom but which didnt even believe in God in the first place. Truman and Eisenhower both railed against the Soviet Unions godlessness while a young student at Yale named William F. Buckley was putting the finishing touches on his book, God and Man at Yale, which among other things made a case for why economic success went hand in hand with social and religious conservatism. Because of the Soviet Unions triple failures of personal, religion and economic freedom, it became easy for Americans to tie the regimes economic failures to their lack of faith, concomitantly highlighting the same connection in the United States as a counterexample. Ronald Reagan probably exemplified this paradigm more than anyone else, appealing to religious conservatives and railing against the Evil Empire. As Friedman says, the whole idea was that communism was a different and failed economic system because it was a different religion.

Today many people in the United States like to joke that capitalism has become a religion. Freidmans book demonstrates that there is more than a shred of truth in that remark. But today that relationship is very different from what it was before. One of the big present conundrums Friedman discusses in the book is why Americans have consistently started voting against their self-interests; voters in states which are the beneficiaries of Democratic social safety nets voting against Democrats for instance, or voters voting against the estate tax even when there is no chance of it ever impacting them. Current thinking is that this opposition to economic policies is rooted in cultural policies; for instance, Republican voters who vote to dismantle Democratic safety nets are actually voting against Democratic policies on immigration or gay marriage. Democrats also like to think that the success of Republican candidates in recent years has come from low-income, mostly white voters without a college education massively voting Republican. But Friedman is skeptical of this premise, and I find his questioning of the conventional wisdom refreshing. As he points out, contrary to belief, the percentage of low-income voters without a college degree who vote Republican has actually stayed fairly consistent between 50 and 60 percent in the last fifty years. In addition, the evidence seems to indicate that social issues matter more to highly educated voters than to less educated ones. So, what explains voting patterns?

In Friedmans opinion, religion which has rarely been discussed as a vote driver should be put back on the table as an explanation. For instance, both in 2004 and 2016, the tendency of voters to vote Republican depended not so much on their incomes as on their religiosity; in 2016, among voters who attended church more than once a week for example, 61 percent of those with higher incomes voted for Trump. The importance of religious conviction also shows up in preferences for economic policies. Opposition to policies like higher taxes, more government and having the estate tax seems to be explained better by religion rather than incomes, and particularly by whether voters are evangelical Protestants. As Friedmans history indicates, evangelical Protestants going back to the Puritans and Henry Ward Beecher are much more likely to believe that success in life is the result of individual effort and agency. This applies to both lower and higher income voters. Thus, its not surprising that they seem to oppose policies that involve government intervention, even when that intervention will help them. The centuries old opposition to Calvinist predestination is alive and kicking.

The major problem we face today is the same problem that people at the turn of the 19th century faced, with some having too much and some having too little. Opposition to communism in the 20th century cemented the importance of free enterprise, but we also must not go too far and forget the currents of religious thought that advocated taking care of those who are unfortunate. As the physicist Freeman Dyson once put it, we need a system that combines the best of both capitalism and socialism: big fortunes for risk-takers and winners and parental leave and social safety nets for the losers. Friedmans book indicates that religious thinking provides a guideline to both actions.

Karl Marx famous called religion the opiate of the masses. Today we would like to believe that in especially countries like the United States, religiosity has gone down. Popular surveys do indicate this. And yet Marx was right about this one. We would like to believe that modern capitalism which has lifted so many out of poverty and made them prosper is a direct result of the great progress in rationality of the 17th and 18th centuries. That is undoubtedly true. But what is untrue is to believe that seemingly irrational religious faith had nothing to do with it. While we continue to be the children of the Enlightenment, somewhere deep inside, we remain in thrall to gods and spirits in a cave.

Review #2

Religion and the Rise of Capitalism audiobook streamming online

This is a well written and informative work on religious economic history. Yet the book does have its shortcomings. For one, the title is misleading as there is very little discussion that deals with the rise of capitalism. Second, and perhaps more curious, is the book’s lack of economic theory, for there is now a robust literature on the economics of religion which could have shed light on the detailed religious developments that the author traces out. Readers might fingd it helpful, then, to sample this material which includes such works as “The Marketplace of Christianity,” by Ekelund, etc., as well as the “Marketplace of the Gods: How Economics Explains Religion,” by Larry Witham. This literature is important, for the many religious figures in the book could be seen as religious entrepreneurs that are attempting to maximize membership and income through captive audiences that must rely on them in a laissez -faire economic world in which government is seen as a rival to the provision of goods and services. Competition wthin the religious community for members isalso barely discussed despite its importance. Millionaire religious hucksters that have mega churches and which use television come readily to mind. So, too, and this comes out of public choice theory, is the concept of rational ignorance and its impact on laity voting patterns.

Finally, I am struck by the lack of any discussion in the book on the nature of belief within a social context. One wishes that the author had discussed Eric Hoffer’s classic tome, “The True Believer,” for the insights that it could shed on how economic issues impact religious belief.

Review #3

Audiobook Religion and the Rise of Capitalism by Benjamin M. Friedman

Also, wrong title. A more accurate title for this book is ‘Christianity and the Rise of Capitalism’. Not accidently, the title of this book is the same as the one by R.H. Tawney, viz., Religion and the Rise of Capitalism, 1922. The book under review by Benjamin Friedman can be thought of as the one-hundred anniversary update edition of the Tawney classic. The book by R.H. Tawney was in part a response to, and rebuttal of, the classic by Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Webers claim was the Protestant Christianity, viz., Calvinism, spurred personal behavior patterns suitable to capitalist organization.

Friedmans thesis is that the way we look at the world today is simply based on fundamental background assumptions based on Christianity without us necessarily being aware of how deeply embedded this influence is but that it still shows in the way we equate economic success with moral perfection. Friedman claims that this underling Christian foundation is at the basis of the baffling and perplexing perspectives that cause people to support economic policies and practices contrary to their own interest such as lower marginal tax rates on the wealthy, elimination of inheritance taxes, deregulation of industry and business. There are parties who benefit by these polices, but not enough to carry an electoral mandate if people were voting their own interests.

Friedmans point is that economic opinion and policy is still informed by the residue of religious thinking but without market participants, economic theorists and policy makers being explicitly aware of this influence. Friedman claims that modern economic thinking is still biased by Christian doctrine without it being explicit. It informs the background assumptions made about human nature and human behavior in formulating economic theories about markets. The assumption of rational individually motivated behavior in economic thinking is informed by the Christian doctrine but Christianity itself is a fragmented religion with many incompatible versions. The implication from Friedman’s account is that economics is partly an empirical science, partly a formal system of rules and in great measure, a philosophical perspective still riddled with metaphysical assertions. All perspectives must be examined, especially the presuppositions contained within ethical and political models such as economics otherwise we become prisoners of the current reigning or even a past orthodox perspective. Just as Freidman can claim that religious attitudes effected economics we can also state that the natural evolution of economics effected religious outlook.

Alternative hypothesis:

Material realities are more important than religious fantasies. Friedman has it backwards. In his hypothesis he is reversing cause and effect. More accurately, economic conditions determine religious beliefs. That is, religious beliefs change in response to economic evolution; they change to accommodate a changing social consensus. Religious beliefs, philosophical perspectives, ethical practices and moral principles as well as notions about the self and human agency all arise from material conditions and our changing understanding of the world. Religious ideas and perspectives do not determine material conditions, they are determined by material conditions. Religious beliefs only magnify and reflect the prevailing social values and customs of the society in which it is imbedded.

My disagreement notwithstanding, the book is an excellent survey of the religious, economic, political and intellectual history of European and American thought from the early modern period forward and is still well worth reading.

I do not agree with Friedmans analysis in that I find it unlikely that market participants, economic theorists and policy makers and influenced to such a significant extent by mysterious unknown forces of which they are unaware. I think it is much more likely that voters are actively manipulated. In one of my own books, I present that thesis that voters are fooled by their own aspirations for a hoped-for better life. They are deceived into thinking that they too could be wealthy if they only work hard enough. This provides a false alignment of values between the working and the wealthy. The working people have also been misled by real history in that there was a time, at least in the U.S. from roughly 1945 to 1980, when increasing overall economic prosperity did filter through society to create genuine social progress, but this was the result of tax policy and regulations. However, this history has been manipulated and used to build support for the untested hypothesis of trickledown economics. This expectation has set in with the sort of intellectual rigidly that takes considerable force to dislodge. I think this is why many voters support Republican candidates promising tax cuts for the wealthy and deregulation even though such policies are of dubious benefit to most people. Most of the wealth created by these means accumulates at the top with wealth disparities in the U.S. growing ever more severe. What is most remarkable is that as the aggregate economy has continued to grow by almost any measure while income levels of working people have continued to fall by almost any measure.

The Republican elites sell these policies to the voting public by talking in the language of aspiration, hope, liberty and opportunity for all when in fact they are pursuing advantage, pleasure, license and privilege for a few. These elites get away with this because social solidarity based on economic status can be reliably and easily undermined by appeals to opportunity, liberty, patriotism, nationalism. Everyone can aspire to be wealthy. The least well-off are fooled into identifying with the most well-off rather than their true peers. The false narrative is that anyone can get ahead with hard work which just is not the state of reality. A narrative of aspiration and hope can easily overtake a reality of unpleasant facts.

Culture wars are generated, not for resolution, but to keep people divided and in constant conflict. This further diverts attention away from the commonalties of class or economic status. This is the social opening that the political right exploits by creating a false identity or alternative solidarity based on cultural issues. They set themselves up as role models of upward mobility for all to emulate with hard work and dedication. This is the sophistry used to get more productivity out of working and middle-class workers. This is how we get billionaire populism. In a society that pushes success and failure down to the individual level with a social premium on success and a social penalty on failure, it is difficult to rally people around failure. It is nearly impossible to bring people together to effect change based on their shared despair and despondency. No one celebrates failure or likes to be identified with it. Shared despair and despondency were the stuff of revolution at one time, but this path has been closed due to the social price one must pay for being identified with this group in a society which values individual success over all other possible outcomes. This path to revolution and reform is blocked. In reality, success and failure are often things that just happen to people owing to structural and systemic factors that get falsely individualized and thus misperceived. It is like trying to rally people on a shared sense of shame. Individuating the pathologies of the social consensus is the key to instituting them as permeant system features.

There is a role for fundamentalist Christianity, but not the one identified by Friedman. It aids by filling social voids and in providing a safety valve to relieve system pressure. Social pathologies and economic asymmetries are addressed with the individualized spiritual solutions of deliverance and salvation. This further undermines the motivation for social action to remedy real social pathologies and frees the policy makers to provide for their real constituents with polices such as tax cuts and deregulation that mean nothing to most workers personally, hurt the economy for the vast majority of middle income people but benefit the wealthiest segments of the population. This provides a double benefit to the wealthy in that these same easily fooled otherworldly fundamentalists form the most reliable worldly voting bloc in favor of these policies.

People are more easily mobilized by appeals to nationalism and greatness than to shared economic status in which individualized failure is stigmatized and social class is ignored. Nationalism is a much easier identification and provides a much wider net than a sense of shared economic, social or class status, which are by definition more-narrow even when they can be called out. This is not an effective appeal in a society that prizes individualism and personal success, especially in economics. The wealthy know that the most important appeal is to the aspirations of these voters rather than to their realities. The appeal is to imagination, or can I say simulation, rather than reality. The real war on reality.

Recommend Books

Galaxyaudiobook Member Benefit

- Free 2000+ ebooks (download and online)

- You can see your watched audiobooks

- You can have your favorite audiobooks

Galaxy audio player

If the audio player does not work, please report to us, we will fix it as soon as possible (scroll up a little you will find the "REPORT CONTENT" button).

0 Comments: